- Home

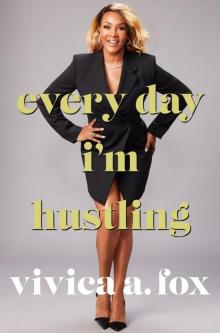

- Vivica A. Fox

Every Day I'm Hustling

Every Day I'm Hustling Read online

Begin Reading

Table of Contents

About the Author

Photos

Copyright Page

Thank you for buying this

St. Martin’s Press ebook.

To receive special offers, bonus content,

and info on new releases and other great reads,

sign up for our newsletters.

Or visit us online at

us.macmillan.com/newslettersignup

For email updates on the author, click here.

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

This book is dedicated to the memory of my late father, William E. Fox.

PREFACE

I don’t know what brought you to this book, darling, but I am so glad you’re here.

Maybe you got knocked down and you need a little help getting back up. Perhaps you invested in loving the wrong person. Maybe you don’t even know where to start on your dream and you see everyone else in this Instagram-filtered world living theirs. I’ve been there.

Let me tell you a secret. When I was a little girl growing up in Indianapolis, no one could say “Vivica.” I used to get called “Vuh-vee-sha” or “Vi-vike-a,” anything but the right way. And, honestly, most folks just couldn’t be bothered. I was so sensitive about my name that I made it easy for everyone else, going by a shortening of my middle name, Anjanetta. “You can call me Angie,” I’d say, like an apology. In life sometimes we run away from the things that make us unique.

I didn’t become Vivica until I came to California and met my first casting director at an audition. I told her my real name, then quickly blurted out my usual, “But it’s okay, you can call me Angie.”

“Why? You have a beautiful name,” she said. “As a matter of fact you should be Vivica A. Fox, so people will always remember you as ‘Vivica’s a fox.’”

And honey, I thought I was gold. By 1992, I’d been on an episode of The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air and landed a spot on an NBC sitcom by the same creator. The show was called Out All Night, and I got to play the daughter of none other than Miss Patti LaBelle. Out All Night was set in a club, so I was meeting musical guests like Luther Vandross, Mary J. Blige, TLC, and Mark Wahlberg when he was just Marky Mark. I made the cover of Jet, and I knew those people back home in Indianapolis could say my name now. I had made it.

Then one morning we all came in for a table read. We’d taped a show the night before, and I thought we killed it. “Yeah, you killed it,” someone said. “The show’s canceled. Clean out your shit.”

They weren’t even going to air the last show. Now, I wish I had a tape of myself crying at that table, because, Lord, it would show how deep and ugly I can go as an actress. I was in such a state that Miss Patti couldn’t believe it. “Child, you crying so much you ’bout to turn white,” she joked. “You’re gonna be all right. You’ll see.”

Here I had one of the most talented and experienced entertainers in history telling me I would be okay, but I couldn’t hear it. I was devastated. I was living in this cute little condo in Inglewood, thinking I’d made it. I’d put two thousand miles between little Angie and the person I wanted to be. And now I was losing it all.

It got worse. I would go on audition after audition, watching my bank account dwindle as each time I would make it to the final callback … and then they’d go with the bigger-named black actress. At the time, Jasmine Guy from A Different World was the “It” girl blowing up. Me, I was just blown up.

Finally, I had to call home to tell my mom I was in trouble. Everlyena Fox spent my childhood working. She was a single mom who held down two jobs to provide for us four kids after my parents divorced when I was four. She believed in two things: work and God.

I’ll never forget the call. I gingerly told her I might need a bit of a loan. “If you can help me out…” She said yes, and I cried. And I told her, “Okay, I’m not going to be calling and asking for money again, so I’ve got to figure this shit out.”

“Write a letter,” Mom told me. “Put it in your Bible and pray about it. He will bring it back to you.”

So I got on my knees. And I wrote this:

I want to be successful. I want to be a star and I want to work as an actress. And I’ve got a taste of things, but it seems I can’t get over the hump. It seems I’m always almost just making it and then coming up a little bit short.

If you could just help me to stay focused and help me to stay positive, I promise that I’ll be good. And do good. And give back.

Maybe you’re feeling the same way. You just can’t get over that hump and you keep coming up a little bit short. For me, the answer came when I asked. And the answer was to get to work.

And keep at it. I worked my ass off—sometimes literally—to get Independence Day, Set It Off, and Kill Bill. I took risks to get Curb Your Enthusiasm and was offered the role on Empire because Lee Daniels liked how I handled myself with the silliness on Celebrity Apprentice. I got to return to the big screen as Jasmine in Independence Day: Resurgence and be the Head Chick in Charge on my own show, Vivica’s Black Magic. My grind don’t stop, and people notice.

Sure, there’ve been failures and heartbreak in relationships. I’m working on that, trust and believe. You can also trust that as a single black actress in my fifties, I understand struggle. I get up every day to fight for my place in Hollywood. And sometimes I’m still my own worst critic, looking at what’s wrong instead of what’s right. Just this week I saw a paparazzi photo of me walking out of something with my arm waving. See, you had your arm up and look at that tummy, I said to myself. You look a little fat through there.

And then I had to say, Snap out of it, bitch. You gotta be your biggest cheerleader. Get out of your own way.

I want to help you as you get out of your own way, too. Now, my language can be what I call “street but sweet”—my friends didn’t nickname me Ghetto Barbie for nothing. But I can also take you to church. The Lord loves a scrappy girl.

I owe this book to my mother, who told me to write down my dream. But this book is not about making a wish. I want to provide concrete, real strategies for realizing—or even just figuring out—your dream.

And I hope it’s a big one. There’s nothing wrong with having big dreams. It just means you have to put in more effort. Some people today think they can swipe right or press send and something can happen overnight, and you don’t have to work for nothing. It’s so different from what I know to be the truth. I have had to work for every damn thing. My mama told me growing up, “You’re gonna work. I don’t care if you think you’re cute. Yes, you are, but your ass is gonna work.”

So take my hand, darling, and let’s work together.

PART ONE

THE START OF OUR HUSTLE

LESSON ONE

IF YOU HANG WITH THE BIG BOYS, YOU’RE GONNA GET KNOCKED DOWN

I wanted to look like a goddess.

This spring the beauty magazine Sheen threw me a party naming me Woman of the Year, so I felt I had to look the part. They had flown me from L.A. and put me up in a lovely suite in the Atlanta Marriott Marquis. I still had a few minutes before I needed to head downstairs to the black-tie gala, so I did one last check in the full-length mirror.

My hair was up high and off my face, and my makeup artist Daryon Haylock had given me a smoky eye, glowy skin, and a bold lip. For a big event we always put just a little glitter on my face, a little shimmer to feel regal.

Instead

of an LBD, I went with a little black Alexander McQueen gown that my girl at Neiman Marcus Beverly Hills, Bani, helped me pick out. A halter-neck, down-to-the-ground stretch-knit, the dress hugged every curve and accented all of my assets. The dress showed off my arms—which you know I had been putting some extra work into defining since I picked the gown—and it had a tasteful cutout to show the cleavage. The girls were sittin’ up proper, I thought, running my fingers over the dress’s jeweled neckline. This wide collar of sparkling jewels was what sold me on the dress. It reminded me of Audrey Hepburn’s diamond necklace in Breakfast at Tiffany’s.

“Woman of the Year,” I whispered to myself, turning to get the whole look. Usually at this age Hollywood tells women they’re going to put you out to pasture. Actually, they don’t really tell you—they just make you invisible. If you don’t get the hint and go quietly, they will knock you down. Time and again, I have done myself the favor of getting back up.

There was a knock at my hotel room door. It was my big brother Marvin with his wife, Thelma, and their eight-year-old son, Myles Ryan. They live near Atlanta, and one of the reasons I was so excited about the gala was that I could share the night with them.

“Looking good, sister-in-law,” Thelma said as I hugged Marvin.

“Right back at’cha, sister-in-law,” I said.

Myles Ryan was so cute in his gray suit vest and blue-striped tie. “You ready to do this?” I asked.

My little nephew broke into his megawatt smile. “Yes, Sparkle T.T.,” he said. He has always called me that, starting when he was a little baby who couldn’t take his eyes off my diamond earrings. I’d kiss his cute face, and he would reach for them and say, “Sparkle.”

When we got downstairs, photographers waited at the entrance to the party. I was posing up, really giving a “She has arrived!” performance, and then I started laughing. I noticed Marvin and his family were standing off to the side, not sure what to do.

“Come here,” I said, waving them in to stand beside me. “This is about you, too. I wouldn’t be here without you, Brotha Marv.”

Flashbulbs went off on the four of us, and I drew Myles Ryan closer to me. There was not an ounce of nerves to this beautiful child, and his megawatt smile shone even brighter in the cameras’ flash. He loved the attention.

“Look at you,” I told him. “You’re a star.”

Myles looked up at me and got this little glint in his eye that reminded me so much of pictures of me as a kid.

“That’s right,” I said, assuring him the same way I would tell myself when I was a kid. “We are stars.”

Let me tell you a story from back in the day.

I was six years old, two years out from my parents’ divorce. My dad was visiting my mom’s home in Indianapolis, and we four kids were all with him in the backyard. My mama had a cute little green house, wood-framed and about a thousand square feet of us kids crowding each other. We were two blocks from the projects, nestled in a long row of ranch houses with just-washed cars parked on concrete driveways.

Everlyena Fox had worked two jobs to buy her own home and live a life of independence. My mother had grown up a West Point, Mississippi, farm girl, used to working from sunup to sundown. Her childhood was all about milking cows, shooing pigs, and picking cotton. School was her salvation. She walked the miles back and forth from school like it was a higher calling, and graduated from West Point High School.

I once asked what parts of farm living she enjoyed. She laughed.

“Nothing,” she said.

On her own with four kids at thirty-two, my mom brought that same dedication to providing for us. And to proving that she would never, ever have to rely on anyone for a single thing again. Especially my father. William Fox was that city boy who got him a good old country girl and brought her up to Indy. They met when she was twenty-one, while she was visiting her older brother in Elkhart, Indiana.

“She had an extreme beauty and poise,” my father, who was eighty at the time, told me, remembering when he and my mother were young. “She was like a Sophia Loren. And I wooed her with my city swag.”

And he broke her heart. I’m a daddy’s girl to this day, don’t get me wrong, but I know he broke her heart.

So whenever Dad visited, my mother made herself scarce, which wasn’t hard for her to do when she was working so damn much. Breakups are never easy, as I’ve learned.

It was summer, and my big brothers, Marvin and Sandy, were playing basketball at the hoop my dad had set up for them. Marvin, our family’s quiet go-getter, was ten. Sandy, the most athletic and mellow of our family, was seven. Our big sister, Sugie, already our Mama Bear at eleven, was left to play mother while our mom worked. That day she was fussing over me, telling me not to run around quite so much or I might get hurt. Marvin’s nickname for me was Cartwheel Angie, because I was always spinning, running, having fun. My mother used to say, “Now, that one there of mine, oh, she’s busy. She always busy.” My mother has a Southern voice that flows slow like honey, and I can hear her telling me, exasperated, “Sit your little hyper self there.”

Dad was shouting pointers at Marvin and Sandy as I watched them fly around the backyard with the ball. Any time spent with my dad revolved around sports, and back then my brothers always got the lion’s share of his time and attention. He’d take them to wrestling matches and Indiana Pacers games at the State Fairgrounds, and the boys would come home thrilled, so pepped up from what they’d seen.

I wanted in.

So I jumped for the ball, yelling, “I want to play, I want to play!” Now, I was a bitty thing, no bigger than a minute, but man, did I take that ball. I was perfection on that court for three, maybe four seconds.

And then Sandy, quiet sweet Sandy, knocked me right over with one jab. I was embarrassed and mad. I ran over to my father, reaching out my arms to be held, a flood of tears about to roll down my cheeks.

“Unh-unh,” Dad said. “Ain’t no crying. Can’t be doing that.”

Hold up. I was the baby of the family—didn’t everyone have to be sweet to me?

Then he told me something that’s carried me through these five decades. “Angie, if you want to hang with the big boys, you’re gonna get knocked down. It’s on you to get up.”

* * *

You’re going to get knocked down. And it is on you to get up.

It’s a lesson you might not see in most self-help or business books, so let me be the one to tell you: Success does not guarantee the absence of getting your ass kicked.

The next time I went in to play with my brothers, damn straight they knocked me down. But I got up. Playing with the big boys made me a better player. And I kept playing with them until I could beat them fair.

Dad started taking me along to Pacers games, and he played basketball with me when he visited. He worked with me on my jump shot until I could nail it and do the Fox family proud. I also got to tag along with my brothers to the Coliseum to see wrestling matches. This was the WWA, an Indianapolis-based early version of the WWF. No frills but plenty of drama. Our favorite was Dick the Bruiser, a bald-headed monster who took on some cocky up-and-comer every week. He’d demolish the new guy as we cheered.

I was trying to fit in so much with my brothers that they taught me all the wrestling moves, from the backbreaker to the headlock. I got put in so many choke holds. If I was cute with them, I got punished. I think that’s what made me so tough.

As I was growing into a jock like my brothers, it made me very different from my big sister, Sugie. My sister will tell it to you like it is, but she’s always had such a sweetness to her that no one called her by her real name, Alecia. It was “Shhhuuuugie,” drawn out like that feeling of eating a piece of pie after a religious fast—or a juice cleanse, whatever you believe in.

Mom made it clear Sug was in charge, and I think that was hard on her as a kid. I know she was proud that my mother felt she could trust her. But Sug had to alternate between being a little mama telling us w

hat to do and a regular teenager who was discovering boys. The Foxes had a reputation for being good-looking, and I thought she was the most beautiful girl in the world. As I followed her lead in all things, she taught me how to be cool. She was popular, and because she was stuck watching me, she would let me tag along with her friends.

One Friday night I went along with her to USA East, the big roller-skating rink in Indianapolis. “We’re gonna teach you how to skate,” she told me. USA East was a wonderland on Friday nights, the lights down low with spotlights of color dotting the floor. I was there with all these big kids roller-dancing with their hands in the air to great music like Stevie Wonder’s “Signed, Sealed, Delivered.” I wanted so bad to be as good as her out there, but I wiped out again and again.

“I keep falling,” I said to her the umpteenth time I landed on my ass.

“Falling is part of it, Angie,” she said. “You’ll get it.”

Now I hear the echo of what my dad taught me about getting back up. Sug was just as much an influence on me. We shared a bedroom and the boys had their room. I let Sug have the big closet and I took the little one. I always gave way for Sug, especially once she got a job. She started working at Target and needed to dress on point. But, oh, I always stole her clothes. She hated that. I was in such a rush to grow up that I didn’t care if I drowned in them. I was a good sneak, but one time I let my friend Sheila Bee borrow one of Sug’s cowl-neck sweaters, back when cowl-necks were really in. “She ain’t gonna know,” Sheila told me. Then her fool ass got makeup on the collar. Sugie knew all right, and beat my butt but good.

Sugie cooked for us, all the things that Mama taught her, and she always stretched the meal with tons of rice. She also made hot-water cornbread exactly to my mama’s Mississippi standards. Now, I’m not what I call a “cooker,” but I saw Sugie and Mama make it enough times to tell you how.

SUG’S HOT-WATER CORNBREAD

Every Day I'm Hustling

Every Day I'm Hustling